Task Force Feature: Building the Fractal Grid - Release #1

Digging into Non-Wires Alternatives with Kyle Baranko

Hello DER Task Force! It is once again time for a Task Force Feature — this time we are very excited to highlight the work of Kyle Baranko’s Grand Prismatic newsletter. In his piece (read the Introduction and Parts I and II), Kyle dives deep into Non-Wires Alternatives and how they fit into the DERs value stack. Wholesale market value and resilience get a lot of love in the discourse, but Kyle rightfully identifies the importance of optimizing our distribution-level systems as DERs proliferate. This is a long and absolutely incredible piece, so we are posting Parts I and II today and will release Parts III and IV on Thursday. We hope you enjoy!

If you are interested in writing a Task Force Feature, reach out to us on Slack!

The Fractal Grid: Introduction

Introduction – The middle child of the value stack – Unlocking Non-Wire Alternatives

The electricity grid is experiencing a paradigm shift changing how, where, and when we produce and consume energy. The Age of the Electron Part II highlighted how Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) are playing a transformative role in this transition in the following ways:

Wholesale Markets: by providing energy, capacity and/or other ancillary services to markets, whether individually or aggregated

Non-Wires Alternatives: by reducing our need for poles and wires or optimizing their usage by being at, or closer to, demand

Resilience: by providing resilience to the end user

All three dimensions have compelling value propositions.

With the rise of variable electricity generation in wholesale energy markets, leveraging the bevy of flexible, digitally-native electrical devices to dynamically balance demand on the bulk grid is becoming increasingly cost effective. Integrating DERs with wholesale markets has received growing political support via orders like FERC 2222 and exhibits tangible, easy-to-understand benefits like eliminating peaker plants and supporting grid emergencies.

Additionally, provisioning on-site resilience – the ability to produce or store electricity during grid outages – is becoming increasingly important as new technologies electrify critical services like heating, transportation, and manufacturing. Resilience also capitalizes on the emotional narrative of American Individualism as marketing campaigns for products like the new Ford F-150 tout the ability to back up homes for multiple days.

In comparison, Non-Wires Alternatives (NWA) seem to be the most inscrutable value stream located in the messy middle between bulk power systems governed by wholesale markets and consumer endpoints at the point of adoption. For a variety of reasons to be explored in this series, NWAs – which will also be referred to as “Distribution System Optimization” – is a sort of middle child, often overlooked and neglected within the DER value stack despite its growing importance.

It is difficult to comprehend, no less sell, the value of optimizing the management and construction of distribution infrastructure because the current institutional environment does not incentivize the telemetry deployment and data processing required to facilitate system awareness at the grid edge. Today, this difficulty manifests as rising delivery costs and interconnection bottlenecks for distributed generation; long term, it will increasingly nudge DERs towards exiting the institutional infrastructure that governs the legacy grid. As the DER market continues to scale and drive down the cost of islanding, microgrid technology may even enable communities to roll back the authority of legacy institutions by owning and managing their own distribution infrastructure, potentially breaking or amending the utility’s century-old natural monopoly on the delivery of electricity.

The focus of this four part series is exploring how and why this transition may occur, beginning with an introduction to fractal patterns and evaluation of community-level resilience and distribution system islanding in Part I. Part II is an assessment of where distribution system optimization fits into the value stack today and how it is closely intertwined with the interconnection process. Part III discusses the dearth of data on distribution infrastructure, the technical requirements for facilitating network awareness, and the implications for DER deployment. Finally, Part IV concludes the series with a philosophical debate on whether the institutions governing the distribution grid must be replaced or simply amended in order to support the energy transition.

Thank you to Bryce Johanneck, Elias Hatem, Colin Bowen, Jake Jurewicz and the DERTF community admins for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this essay series.

The Fractal Grid: Part I

Grid granularity – Self-similarity – Community microgrids

A futuristic grid driven by DERs will require a structural shift from traditional hub-and-spoke systems to fully distributed networks. What does this mean in practice and why is network structure important for the energy transition?

There are three basic designs of distribution systems – radial, looped, and networked – determined by topology: how the poles, wires, and substations crisscross a given service territory. These terms define a gradient describing the grid from most simplistic and least fault tolerant (radial) with many spokes protruding from few central hubs, to most complex and fault tolerant (networked) with many interlocking loops and spokes per hub distributed more evenly throughout the network. Because networked systems require building more infrastructure, they are expensive and predominantly found in population centers where the costs of added redundancy can be spread over many consumers. Cheaper radial systems cover the vast, sparsely populated areas of the country; measured in total line miles, the majority of the grid is technically not a network.

In addition to geography, network structure also depends on scale or granularity as measured by the power flowing through wires and their proximity to the final point of consumption. As shown in the visualization above, more simplistic networks tend to emerge at lower voltages closer to where power is distributed to consumers, or in other words, at high granularity (see the little houses on the left). Networked grids with high fault tolerance tend to appear at larger scales, on the transmission systems of bulk grids where it is cost effective to ensure that entire neighborhoods, towns, or regions have multiple avenues to electricity in the event a line goes down.

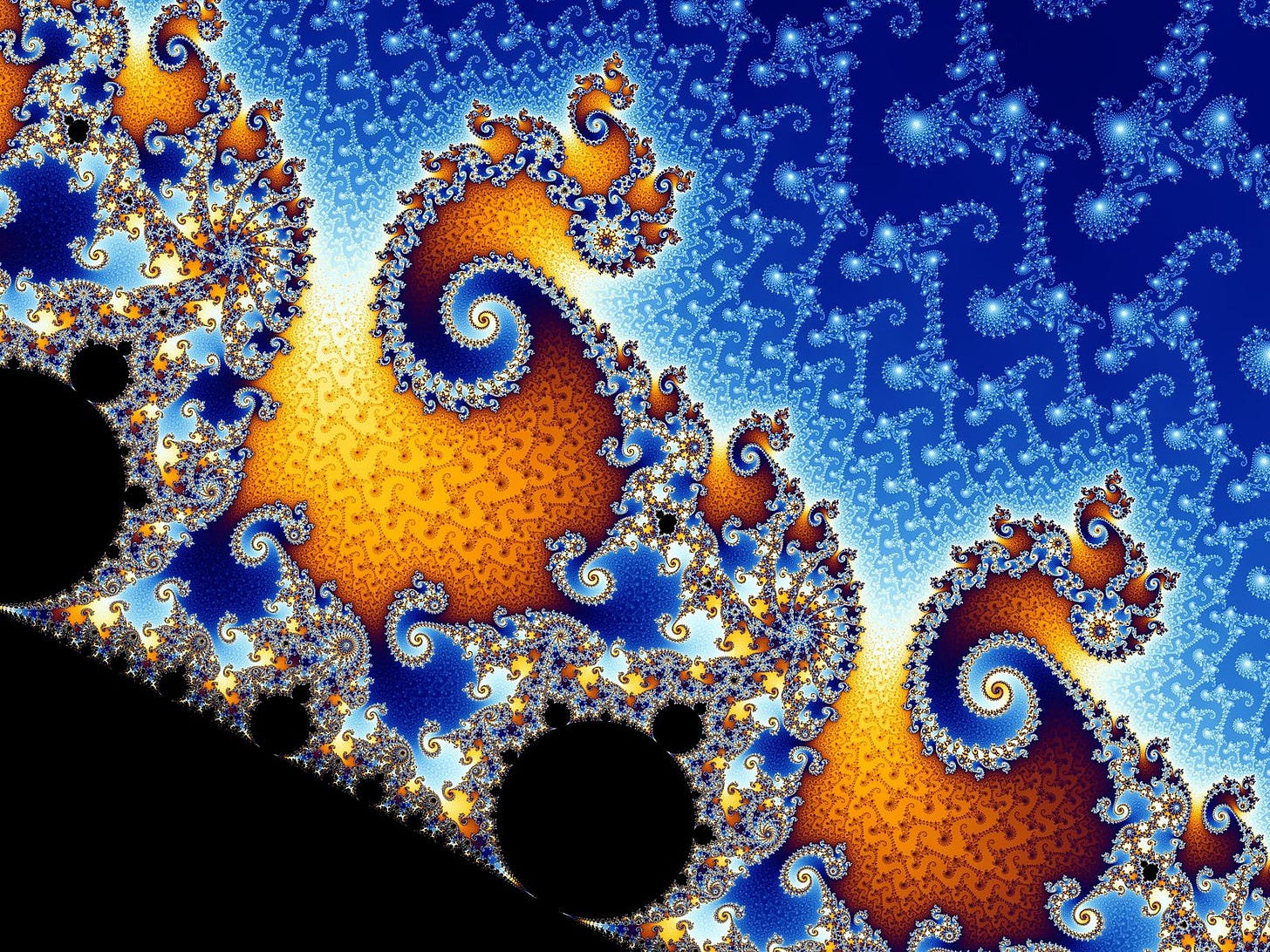

“Fractal” is a useful term to describe these grid characteristics because it offers a formal way to analyze network structure at different granularities. Originally coined by Benoit Mandelbrot, fractals refer to patterns that exhibit self-similarity or recursiveness (i.e. looks roughly the same) at different scales. They are properties of many different disparate naturally-occurring phenomena, from coastlines to broccoli (notice how the structure of a tiny broccoli floret mirrors the shape of the entire stalk). Additionally, fractal systems are typically associated with resiliency due to their self-similar structure and ability to behave independently at every level of granularity.

The network structure and technologies of today’s electricity grid exhibit limited fractal-ness. Some combination of a highly networked grid with renewables, storage, and gas generators appears to be a winning formula for delivering cost-effective resilience at both the ISO and microgrid levels. But as we move up the grid from resilient systems within homes, business, and campuses to the control room of an ISO, we see a change in structure and functionality at the intermediate distribution levels; they are predominantly radial and incapable of operating independently.

So investments in the hallmarks of structural resilience appear at the largest and smallest scales of the grid but they are not truly self-similar fractals; to be fractal, resiliency would be distributed evenly throughout all hierarchies to optimize not just for uptime on the bulk system and end nodes, but at the intermediate layers constituting the neighborhood or community level as well. Distribution networks serving these communities rarely, if ever, have the capability to island. By implication, resiliency is an all or nothing proposition for most of the population: you either pay for a backup system or are completely beholden to the bulk grid.

Do we need a truly fractal grid? If we can power homes and critical businesses when the transmission system goes down, why should we target resiliency within entire distribution networks?

This SunRun whitepaper, published in 2021, proposes distribution-level resiliency solutions for communities affected by wildfire-induced public safety power shut offs in California and paints a compelling picture of the benefits provided by a truly fractal grid. SunRun envisions a future where enough generation capacity and supporting hardware has been deployed on distribution networks to operate independently as needed, providing community resilience during service interruptions and load shaping services during normal conditions. This futuristic network is intelligent, in that it can smoothly transition between interfacing with the transmission system and operating independently as a snack-size ISO, coordinating the services of a diverse portfolio of privately-owned DERs through market constructs.

Several fruitful themes are packed into this vision. By operating at the neighborhood level, even those without the financial resources or technical means to install an on-site DER can access resilience when the bulk grid goes out; the community solar plant can still provide power to local customers, and neighbors with backup systems can still share or trade power. This creates a more equitable distribution of resilience while maintaining private ownership of assets through a method of centralized coordination by the Distribution System Operator (DSO) and decentralized control by community stakeholders. It also provides a community with the optionality to exit the transmission system if, or when, it is in its interest.

What is also captivating is that the robust system awareness required to run this community microgrid maximizes the value of distribution grid infrastructure. As we electrify heating and transportation, squeezing every watt out of increasingly strained wires, substations, and pole-top transformers will be essential; the key question is whether the telemetry and software deployment necessary to provide this degree of flexibility is cost-prohibitive. However, as grids continue to see delivery charges rise as a proportion of total costs, investing in these sophisticated islanding capabilities may soon become economically competitive with the status quo – especially in areas with frequent service interruptions.

The Fractal Grid: Part II

Pricier Wires – The price signal chimera – Interconnection bottlenecks

In Cheaper Energy, Pricier Wires, Duncan highlights how delivery costs have become proportionally greater than the cost of generating power on many electricity bills throughout the US. This trend reflects the importance of optimizing consumption and generation at the grid edge in order to reduce the cost of delivering power, a service that Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) have the technical capabilities, yet limited financial incentives, to provide.

An advantage of DERs is that they can be programmed to provide a variety of beneficial services, comprising a full “value stack”, because they are located at or near final points of consumption. Subsequently, to reach their full potential, this value stack should offer a suite of complementary price signals so asset owners can smoothly arbitrage between revenues from different levels: wholesale markets, distribution system optimization, and community or on-site resilience. Even now, with many fractured and arcane program compensation structures throughout the stack, co-optimizing between multiple levels increases the likelihood of deployment; paying back the upfront cost of a resilience-focused asset with market revenues or obtaining marginal resiliency benefits from an asset primarily deployed for financial reasons can help a project pencil. The deployment rationale depends on the particulars of each asset, as load shifting devices like smart thermostats cannot provide on-site resilience and there isn’t as much of an economic or climate case for diesel generators. But overall, the ability to co-optimize between different value streams should enable DERs to meet the most pressing need at each temporal and geographical juncture on the grid, creating a virtuous cycle where local price signals stimulate DER adoption and alleviate the constraint until grid conditions evolve and form new price signals.

However, consumers considering adding a DER have limited mechanisms to access the full stack because the quality, unity, and form of the available price signals are complex and clunky. To reflect the full cost of generating and delivering power, as well as the value of modifying behavior to reduce these costs, any given DER receives a smorgasbord of static time of use rates, demand charges, and baseline methodologies depending on the particular utility, ISO, and program. Sometimes, price signals even contradict one another (case in point: co-optimizing time of use rates and baselines). Nowhere are price signals more static and ambiguous than those reflecting delivery costs from the distribution grid, which materialize as top-down, bespoke demand response programs for short-term constraints and vague delivery charges and NWA pilot projects for long-term constraints.

The key reason these price signals are of such poor quality is that operating the network in real time is entirely independent from interconnection analysis, which determines whether new sources of generation or load will violate the constraints of the equipment serving the site. The essence of NWAs is to circumvent the need for upgrading grid infrastructure in response to an interconnection request by maximizing the usage efficiency of existing poles and wires. This can be done by using the flexible consumption or generation offered by new or existing DERs to modulate power flow on distribution networks and avoid the constraint. Suboptimal usage and awareness of existing distribution infrastructure limits interconnection. If five homeowners on the same secondary circuit want solar but their shared transformer can only handle the maximum generation of three, two homeowners don’t get to interconnect their DER even if they’re drawn by the resiliency benefits or financial incentives. However, if one or more homeowners use batteries to modulate the generation of their solar + storage systems and avoid the constraint, it could make economic sense for all without requiring an upgrade.

Enabling these types of projects to proceed requires embedding the price signals for load shaping with the interconnection and distribution planning processes. This would enable my rooftop solar proposal to distribute mini-RFPs to the stakeholders on my local network to see who might be willing to add a DER in a strategic location or modulate their load for the right price. By the same token, a utility considering larger infrastructure upgrades could beam out RFPs to DER developers for coordinated deployment and operation of flexible devices. And some do.

However, current interconnection studies are primarily performed via physical site visits, emails, spreadsheets, and creaky, siloed power flow software. Some tools like hosting capacity maps alleviate the initial tediousness and have been folded into the interconnection process to a certain extent, but as many developers can attest, interconnection is a slow and painful technical process that takes several months to complete and often ends with an upgrade fee that breaks the project. Additionally, most of the few recognized NWA opportunities do not get implemented because the opaque cost-benefit analyses completed by utilities routinely deem decentralized solutions to be more expensive and less reliable. Even in New York’s Value of Distributed Energy Resources tariff, arguably the closest practical implementation we have to a theoretical ideal, the Locational System Relief Value (LSRV) is not available for all DERs and is completely at the discretion of the utility.

In Justin Gundlach’s seminal paper on the value stack, notice how distribution system capacity value is updated roughly every decade.

As electrification and deployment of distributed generation impose service upgrades, the current processes for distribution interconnection, planning, real time network management (via ADMS), and real time DER management (via DERMS) should fuse together to evolve past siloed, project-by-project analyses into a true dynamic system of constraint identification and alleviation through the cheapest possible means. But today, not only does locational value trickle into the value stack, but the fragmentation and opacity of these services stymies DER installation. When comparing the state of interconnection and NWA assessment to the exponential demand forecasts for EVs, solar, storage, heat pumps, and other DERs produced by every market research firm, DER growth seems more quixotic than inevitable.

To break this barrier, utilities need greater awareness of when, where, and how flexible energy devices can squeeze greater efficiency out of their infrastructure and ensure the trustworthy coordination of decentralized assets. This requires data.

Parts III and IV to be continued Thursday…