The electrotech revolution in 10 charts and not too many numbers

The big picture of the energy transition in a few snapshots

By Daan Walter, Sam Butler-Sloss, and Kingsmill Bond of Ember. For more, check out Ember’s Electrotech Revolution Substack.

________

2025 was a year of new electric thinking. We saw many energy analysts and writers argue that there is more to the energy transition than just a shift from dirty to clean energy. It came in the form of McCormick and D’Amico’s The Electric Slide, to the IEA’s declaration of an Age of Electricity, to growing discussion of electro-industrialism, the rise of a New Joule Order, and the widespread use of the term electrostates, a term we introduced two years ago that gained broad uptake last year.

We laid out the facts in our September report, The Electrotech Revolution, which we also presented at DERVOS last fall. As we enter 2026, we compiled ten key insights from our work that we think are particularly important this year.

1. This is a technology revolution

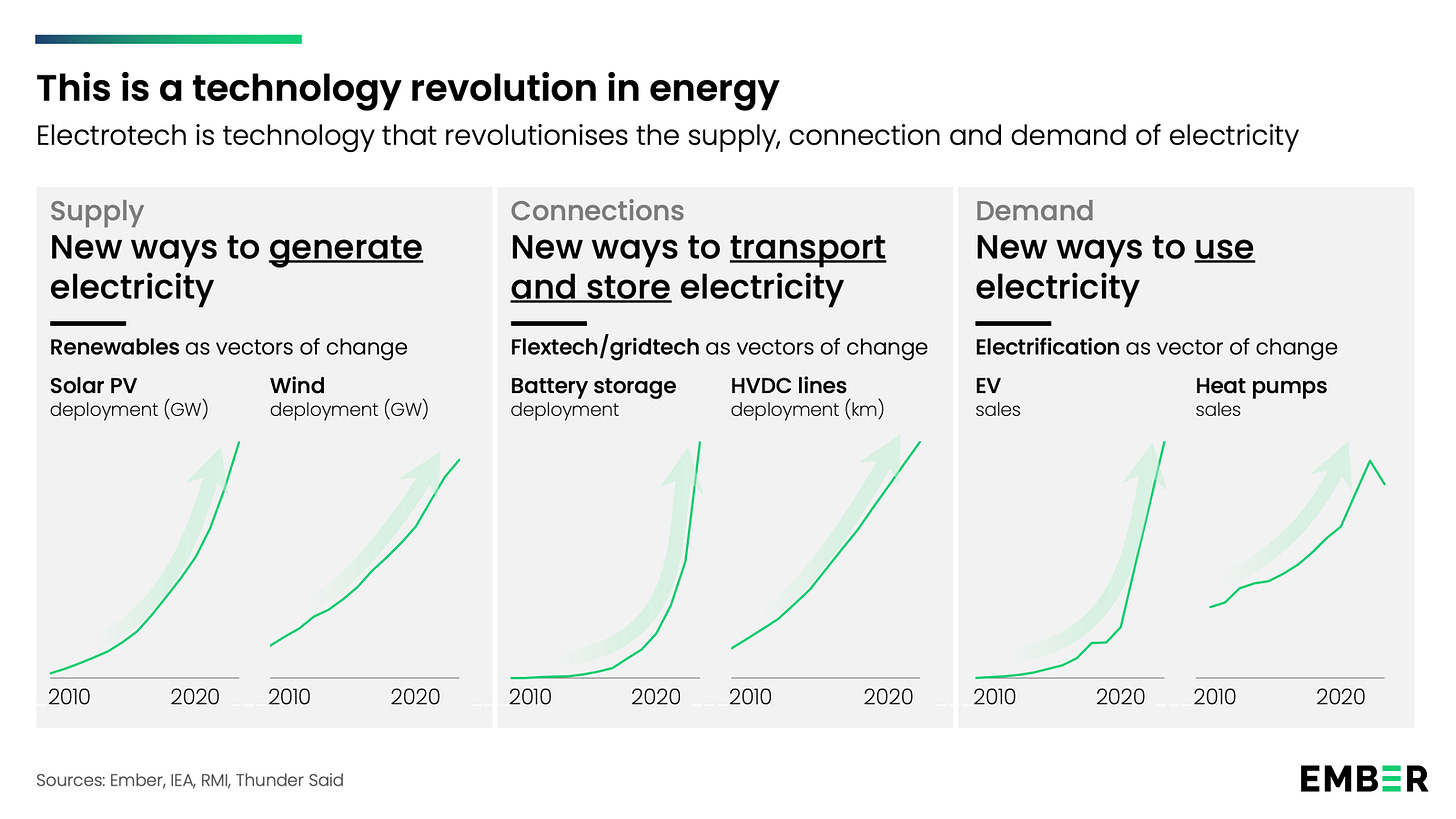

The energy system is not just decarbonizing, it is entering a new technological age. A new generation of technologies is coming together: on the supply side technologies like solar and wind, demand technologies like EVs and heat pumps, and connection technologies like batteries, grids and software.

Each of these technologies is falling in price and rising exponentially in deployment. Individually, each is disruptive. But together, they form something more powerful. As supply finds demand and connections enable both, they reinforce each other on the way up. This is why we speak of not just a transition but a technology revolution.

This matters for 2026. Even as decarbonization slips down political agendas, the self-reinforcing nature of this technological transition does not stop. The revolution has its own momentum.

2. It brings energy abundance

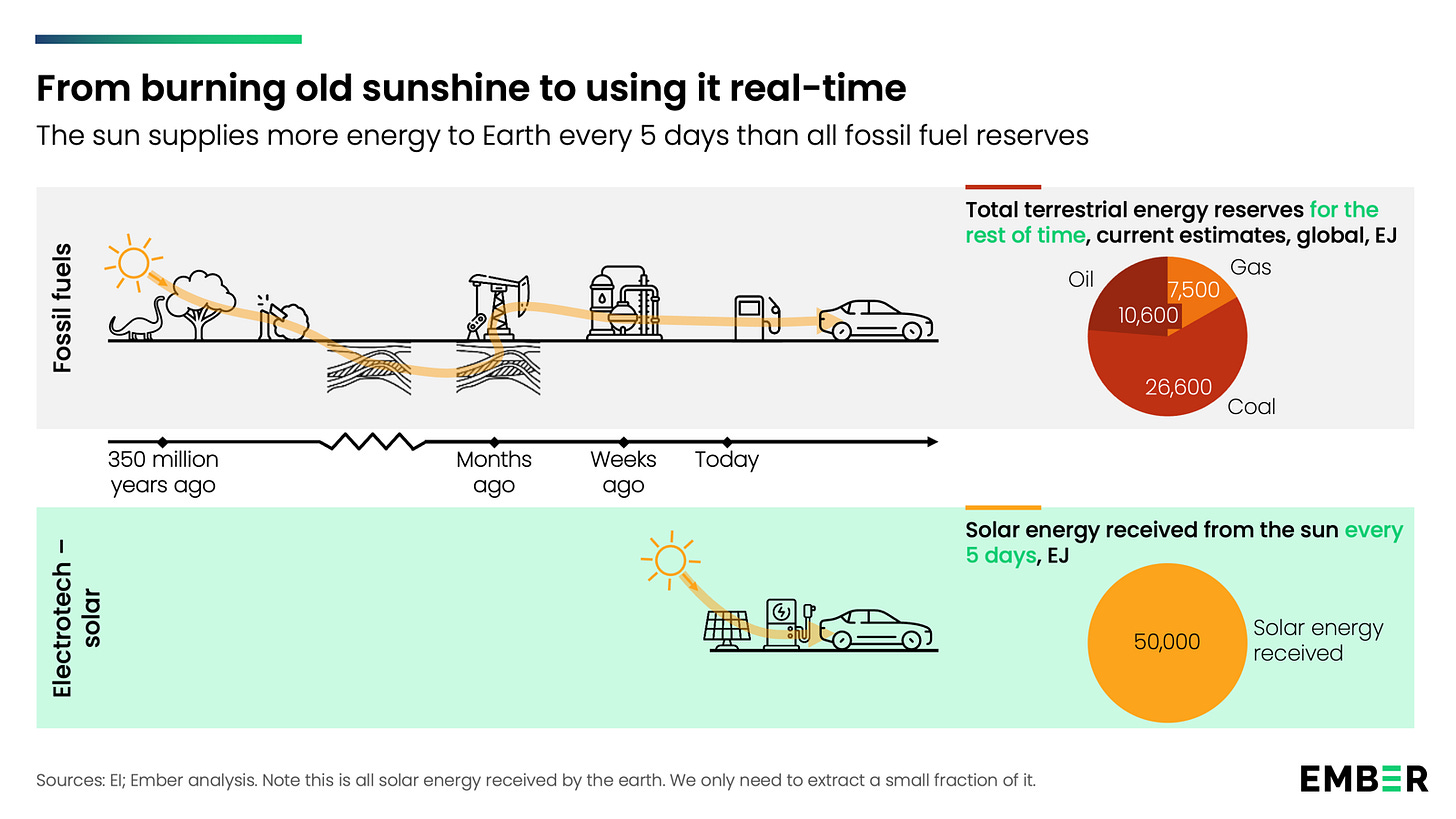

Human history has seen only a handful of leaps in how much energy is at our disposal. Foragers relied on muscle and fire. Farmers unlocked the energy stored in crops and livestock, multiplying available energy by a hundred. Fossil fuels gave us another fifty-fold increase by tapping ancient sunlight buried underground.

Electrotech promises a similar leap. The sun delivers more energy to Earth every five days than all our fossil fuel reserves combined. As we move to tap into this solar resource, our energy system not only becomes more abundant, but also more immediate; moving from burning old sunshine to capturing it in real time. This is a shift from foraging fossil fuels to harvesting the sun.

As we are sure to see a year full of energy abundance debates in 2026, it is worth noting which path actually delivers on that promise.

3. It has been a long time coming

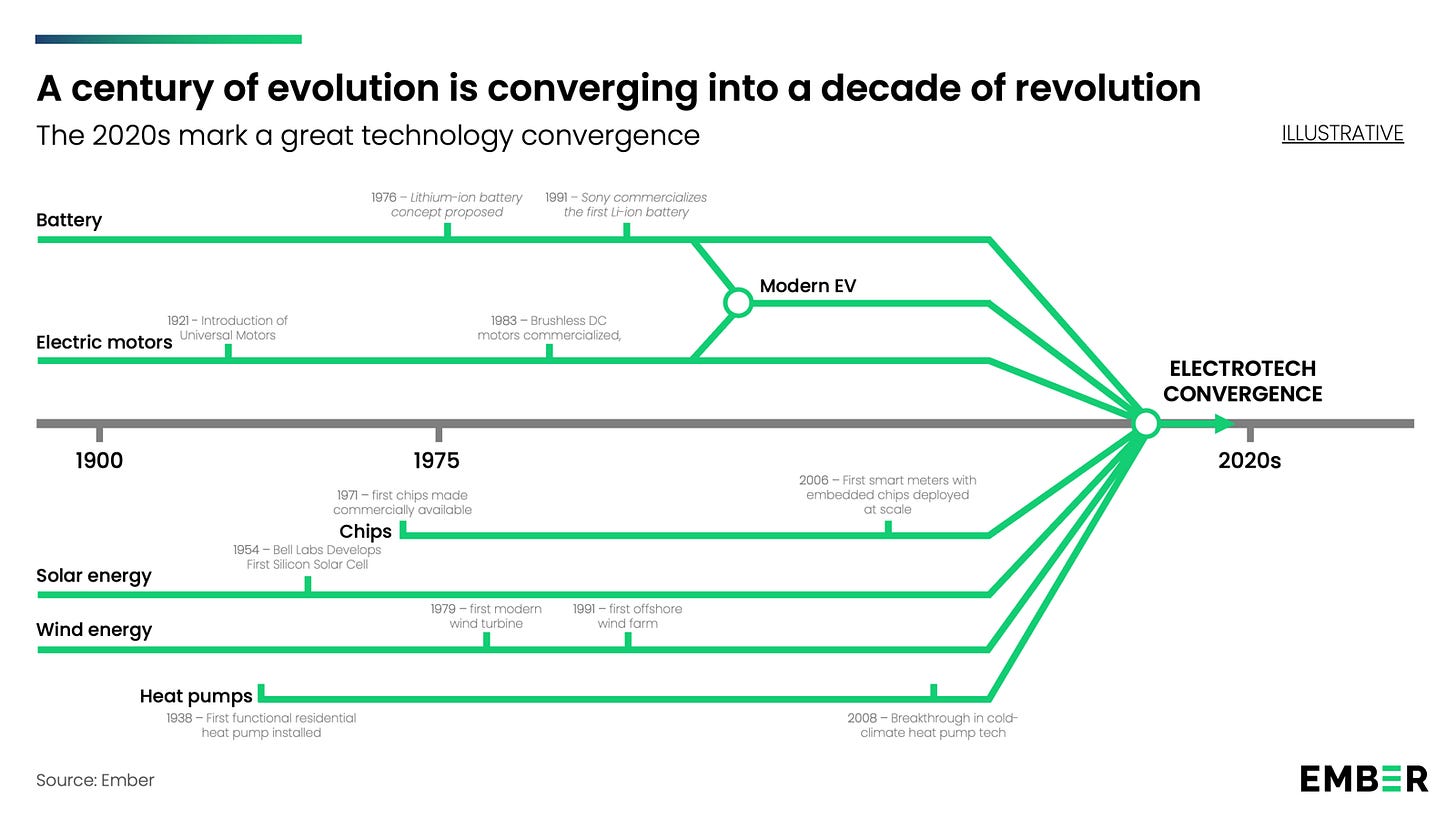

The rise of electrotech is not a recent trend. It has been coming for over a century. Electrification began in the 1880s, when electric lights and motors started replacing flame and steam. From there, electricity demand grew at 5-7% annually after 1900, as lights, industrial machinery, and household appliances spread across the developed world.

The mid-20th century brought televisions, refrigerators, and washing machines into homes. Then came the information age—semiconductors powering mainframes, then personal computers, then smartphones. The clean lab manufacturing techniques developed for chips eventually made mass production of solar panels and battery cells possible.

Now a century of evolution is turning the 2020s into a decade of revolution. This trend has been running longer than any administration or political setback. It comes with a century of momentum.

4. It inherits the momentum of the IT revolution

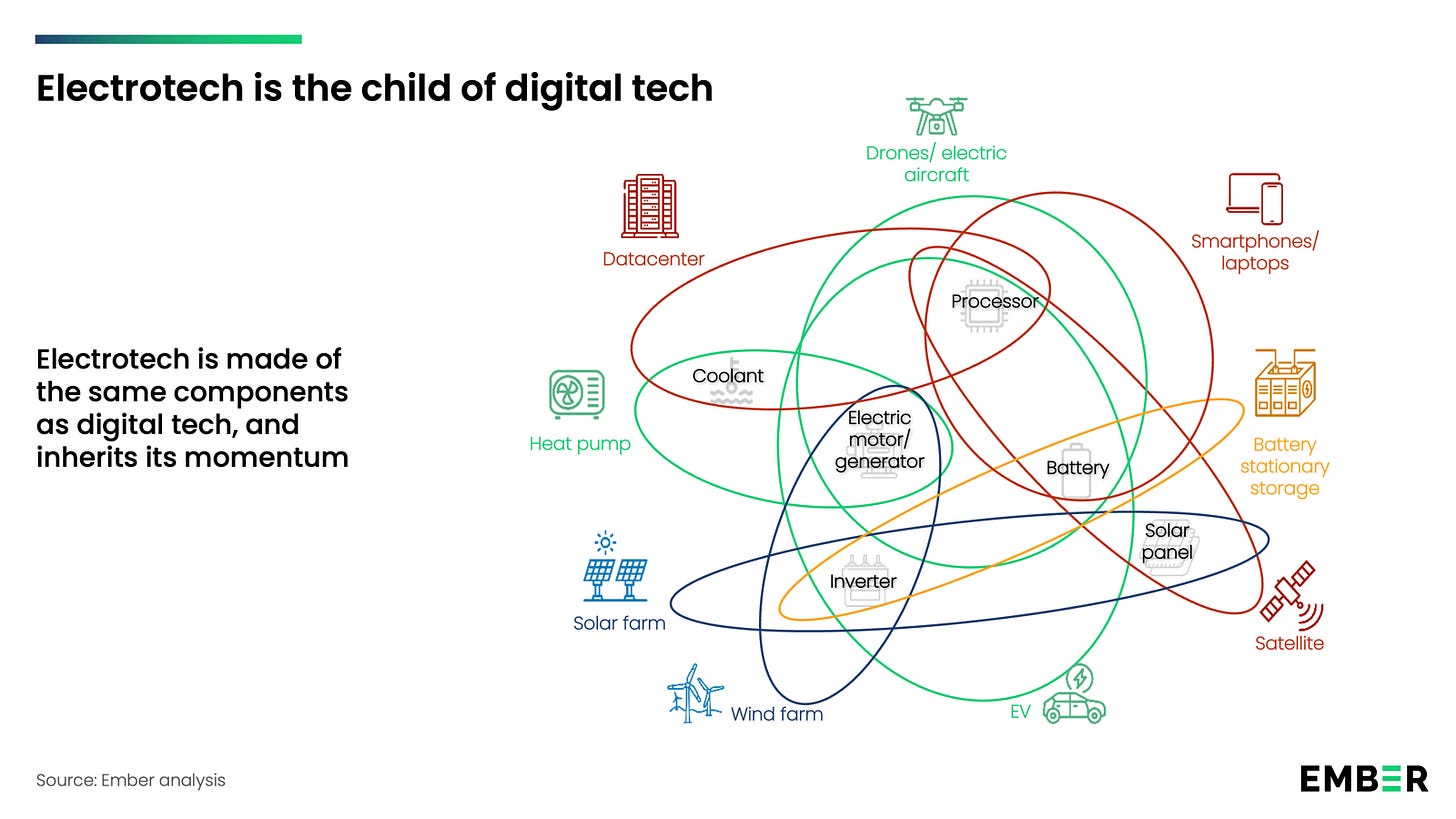

In many ways, electrotech is a child of the IT revolution. The precision processes that mass-produce chips and smartphones now build battery cells and solar panels. The same factories, often with the same workers trained by firms like Apple, now power electrotech’s rise. As McCormick and D’Amico argue in The Electric Slide, the tech stack underpinning electrotech is essentially the same as for digital technology. There is more in common between a laptop and a solar panel than between a solar panel and a gas power plant.

This explains why electrotech scales so fast: it inherits decades of manufacturing know-how and cost curves from IT.

It also reveals a strategic paradox visible in 2026. IT hardware and electrotech are the same industrial family. They share supply chains, manufacturing capabilities, network effects, and require the same abundant electricity. Building one without the other is incoherent. The current Trump administration push for AI datacenters and manufacturing automation while throttling EVs and solar exemplifies this disconnect. So does the EU’s embrace of electrotech even as it inhibits the AI rollout with complex regulation. Today’s new information technologies and electro technologies feed off each other. Those that starve one will weaken both.

5. The ceiling of the possible is far above our heads

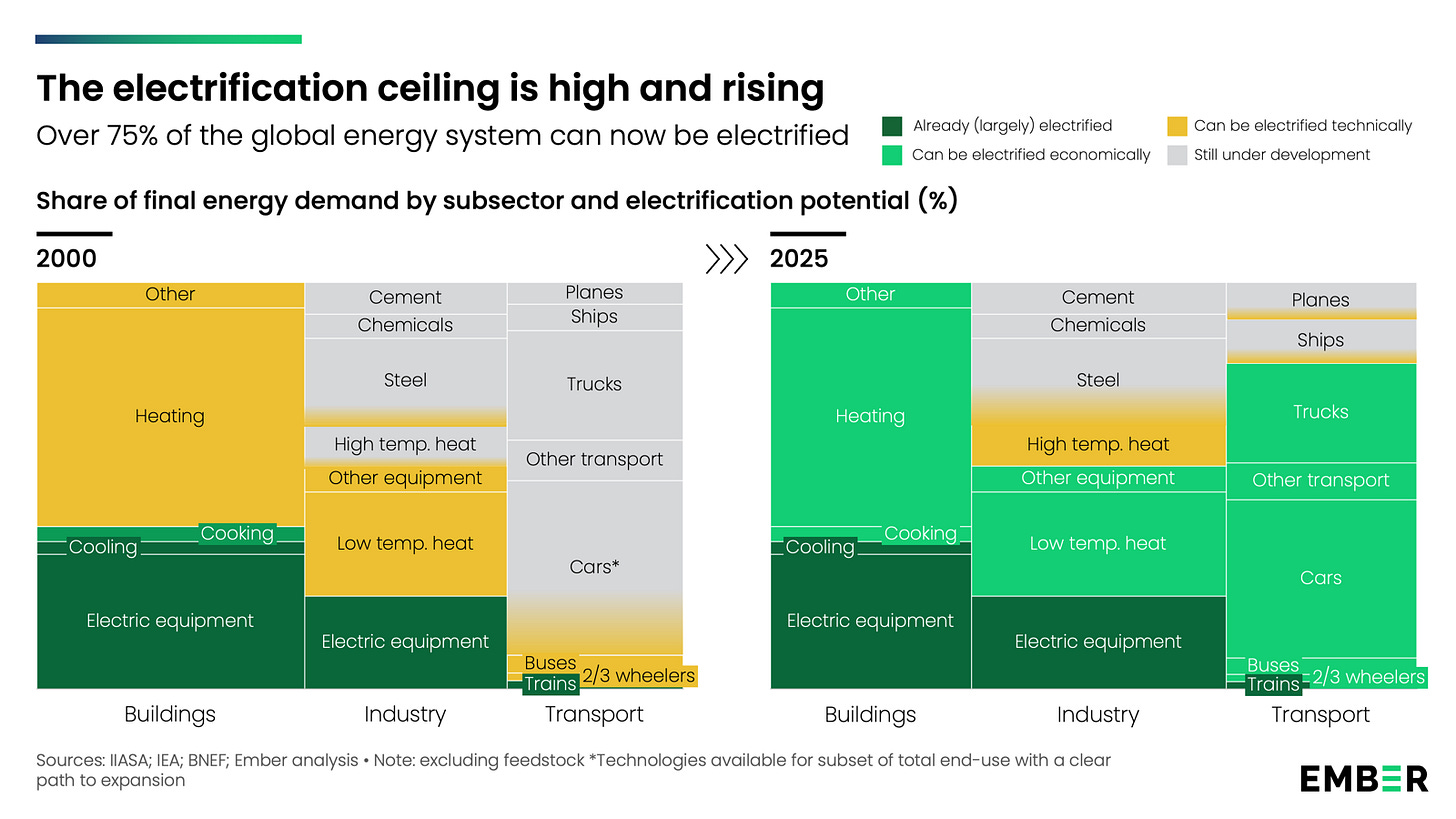

We are nowhere close to the technical limits of electrotech. We already know how to run grids with 70-80% renewables at costs comparable to fossil fuels. We can electrify around three-quarters of final energy demand with technologies that exist today or are nearly commercial. Renewables and electrification could more than triple from current levels before reaching what we know is achievable.

And the ceiling keeps rising. As frontrunner regions push grids toward 90% renewables and innovators bring electrotech into aviation, shipping, and heavy industry, the technical frontier expands. By the time most catch up to today’s ceiling, the pioneers will have raised it once more.

In 2026, expect more narratives about slowing deployment in leading markets. But most of the world is still catching up. This catch-up dynamic alone sustains momentum for years to come.

6. The physics of change

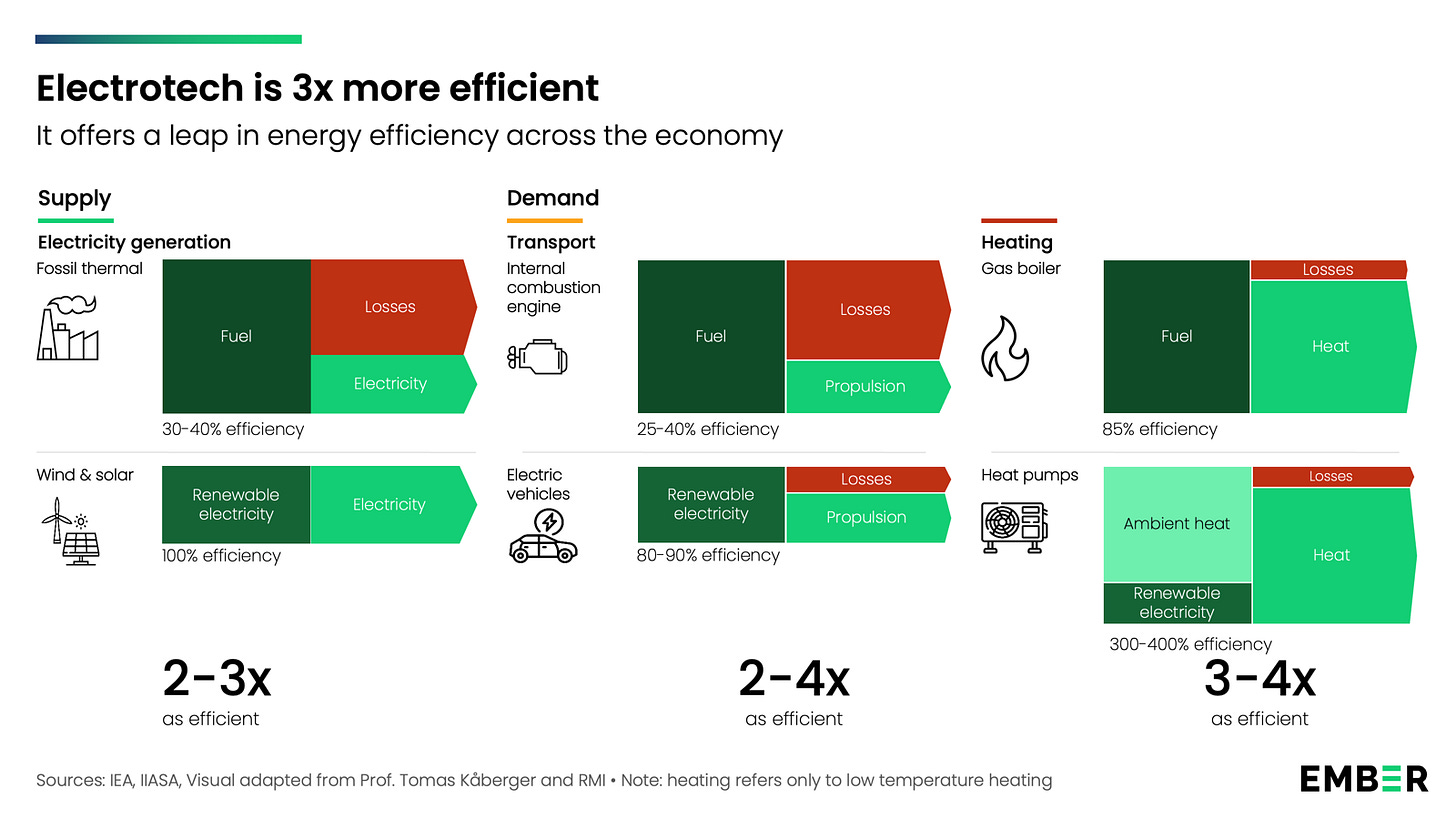

Fossil systems are inherently wasteful, losing about two-thirds of their primary energy to heat and friction. Electrotech is built on efficient electricity: EV drivetrains convert around 80-90% of input into motion, while heat pumps deliver three to five times more heat than the electricity they consume. Wind and solar avoid thermal losses altogether. Physics itself tilts the system toward electrons.

This efficiency advantage extends to materials. Electrotech uses eternal sunshine and wind rather than one-time use fossil fuels; therefore it needs roughly 50 times fewer raw materials than fossil equivalents. This gap widens as innovation continues to improve efficiency and reduce material requirements. We should expect 2026 to be another year of such innovations and commercializations—sodium batteries being one example to watch this year.

7. The economics of change

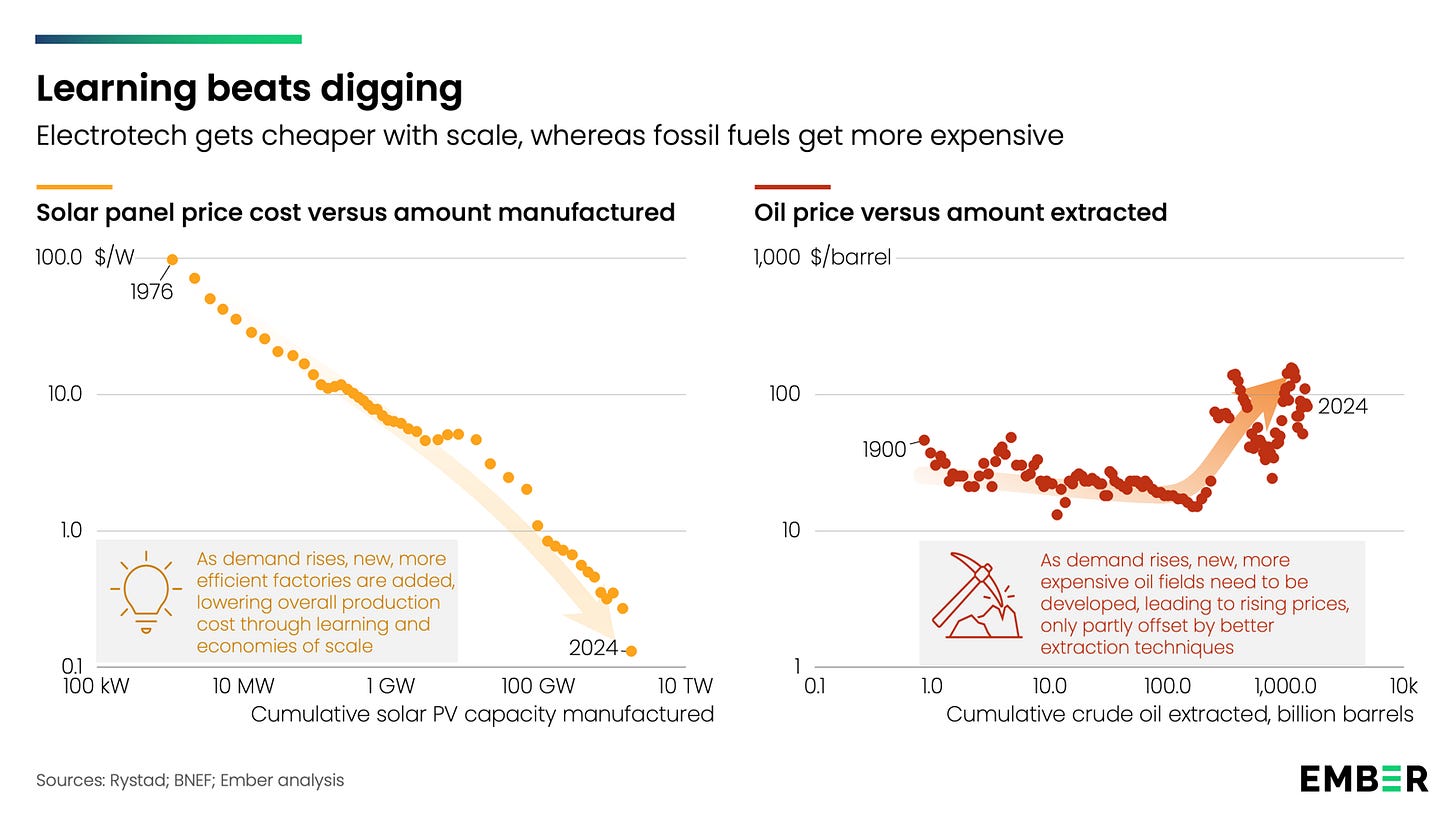

Electrotech and fossil fuels follow opposite economic trajectories. As demand for electrotech rises, new, more efficient factories lower production costs through learning and economies of scale. Solar, wind, and batteries sit on learning curves with costs falling about 20% per doubling. Solar module costs have dropped 99% since 1980, wind by 80%, batteries by 99%.

Fossil fuels work differently. As demand rises, new, more expensive fields must be developed, driving prices up. After decades of these opposing trajectories, we have recently hit cost parity for key electrotech—solar, battery storage, and EVs. Today that means solar-plus-storage in India at $40/MWh and Chinese EVs below $10,000.

This matters acutely for 2026. Affordability is the dominant concern across politics and policy. Five years ago, affordability pressures would have pointed toward fossils. Today, they point toward electrotech. The crossover has happened. The cheaper path is now the electric path.

8. The geopolitics of change

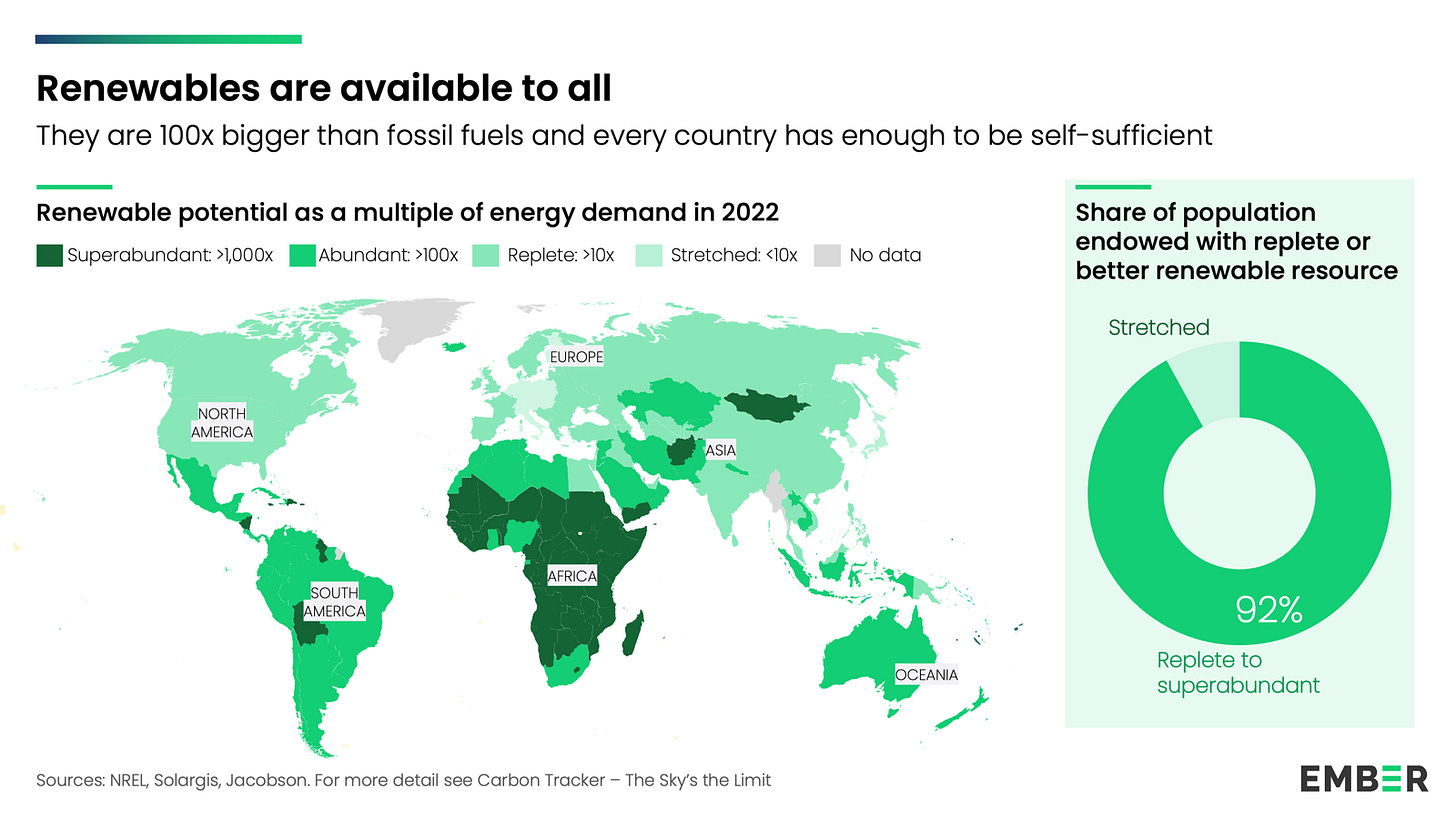

Three-quarters of the world relies on fossil fuel imports. Get cut off, and your economy grinds to a halt. Countries have fought wars over energy access and structured foreign policy around securing supply.

Those risks are rising. Trade tensions are escalating. Geopolitical fractures are deepening. In this environment, every country is looking for alternatives.

At some point, they will look up. The sun delivers energy everywhere. 92% of countries have the potential to generate at least ten times their own energy demand from domestic renewables. With electrotech, every country can become energy independent.

If 2026 is indeed going to be a year of rising geopolitical tensions as many expect, we should expect countries to accelerate electrotech deployment as a strategic priority. Those that sow electrotech will reap sovereignty.

9. Electrotech is a tool for rapid development

For decades, development meant following the fossil path. Rich countries burned coal and oil to industrialize, and emerging economies assumed they would need to do the same. Electrotech allows them to skip that step entirely.

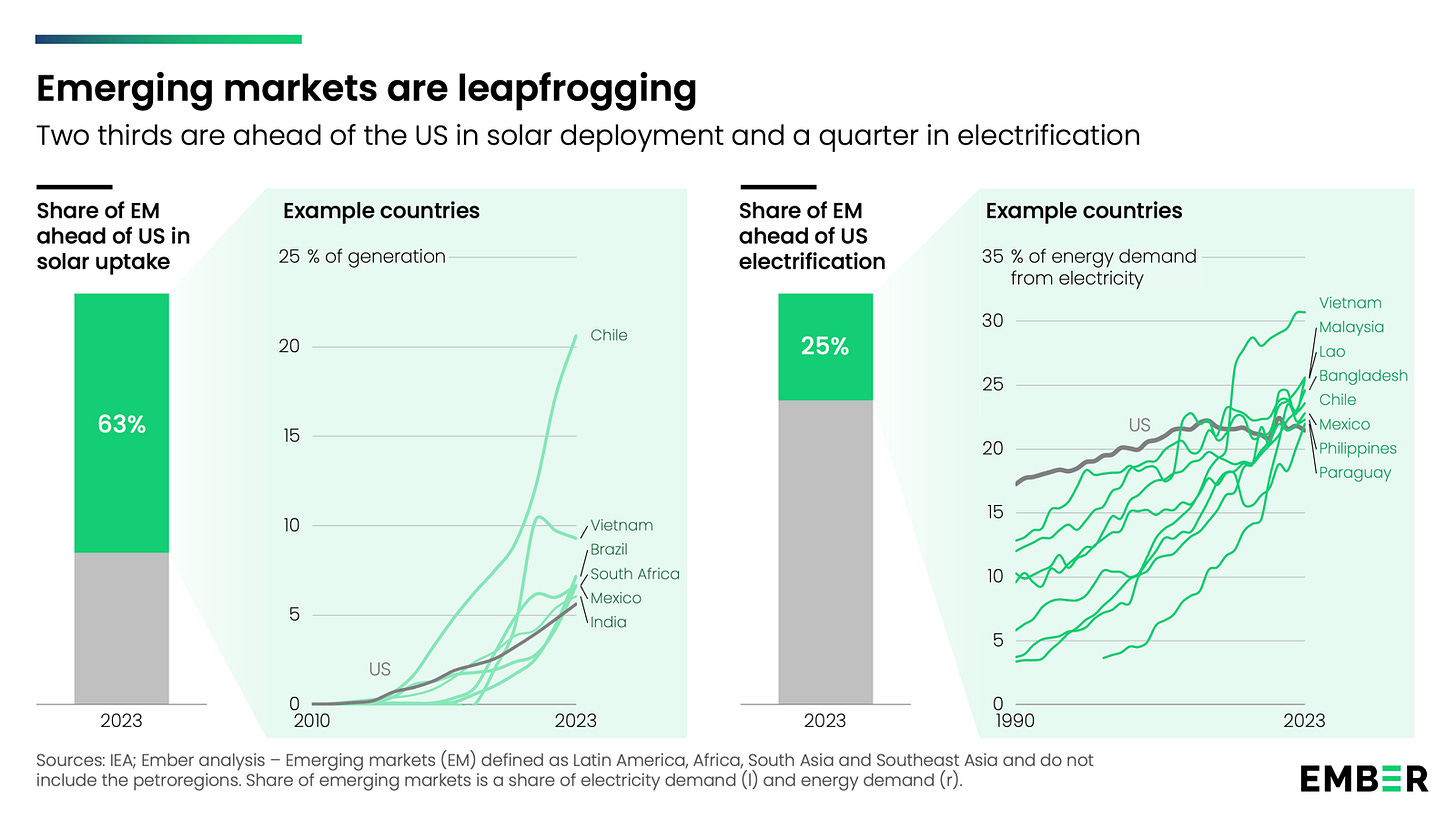

The fastest change is now happening in emerging markets. ASEAN leapfrogged the US in electrification in 2023. Solar deployment has surged across Asia, Latin America, and Africa. In many countries, solar has gone from the smallest to the largest source of new capacity in less than a decade.

The pattern makes sense. Some 80% of the world’s population lives in the sunbelt, where solar resources are abundant and cheap. For countries building energy systems from scratch or expanding rapidly, solar plus storage offers a faster, cheaper path than fossil infrastructure. Development no longer requires a fossil-first pathway. Electrotech is becoming the foundation for growth.

We should expect more emerging market leapfrogs in 2026 as well as a pullback from fossil fuels. As solar and storage costs continue to fall, emerging economies will increasingly look to exit expensive LNG contracts in favor of domestic renewables.

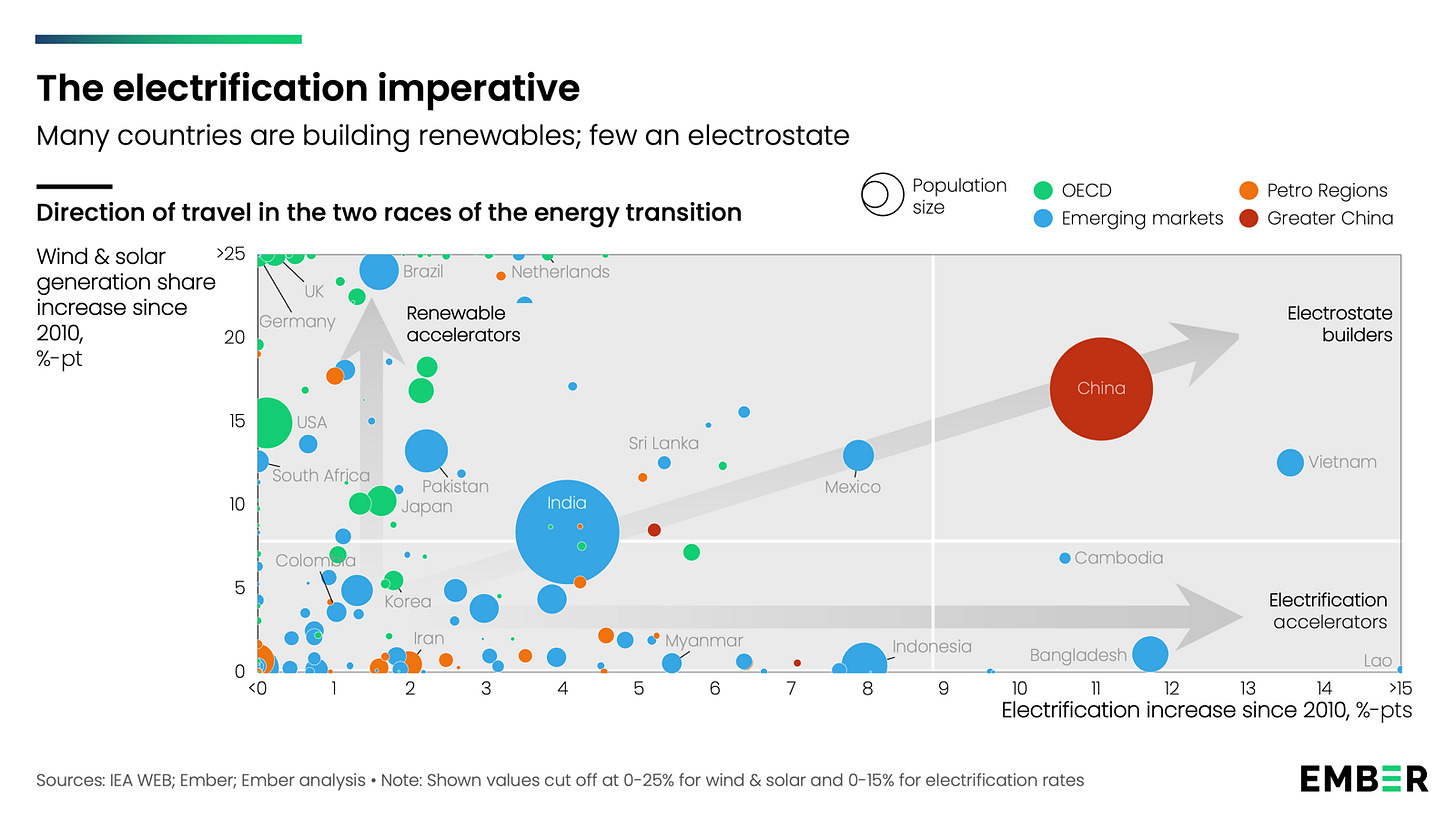

10. Electrification is the geopolitical differentiator today

The world is rapidly building new electricity supply. Solar and wind capacity is being deployed at record pace. But supply alone does not determine competitive advantage. Today, the differentiator is electrification; putting that new supply to work by electrifying transport, heating, and industry.

China has grasped this. It is scaling both supply and demand simultaneously: solar farms and EVs, wind turbines and industrial electrification. This approach, which we call the electrostate model, uses domestic markets to drive down electrotech costs and improve quality, then capture export markets with superior products.

The West is deploying substantial new supply. But electrification of demand has lagged. Solar and wind without EVs, heat pumps, and industrial electrification is an incomplete strategy. As we move through 2026, the question is whether Western economies will match China’s integrated approach, or continue building only half the system.

Entering the second half of the decisive decade

For the first time, humanity can harness the power of the sun directly, at scale, and in real time. After a century of evolution, electrotech is breaking through in a decade of revolution.

The 2020s are this decisive decade. This is the decade when manufacturing reaches global scale, when uptake s-curves enter their steep ascent, and when costs cross over from more expensive to cheaper than incumbents. We have just passed cost parity for solar, batteries, and EVs. From here, the economic logic only strengthens—as do the physics and geopolitics drivers of change.

Countries and companies that recognize this shift will shape the next era of global competition. Those who resist will find themselves left behind. The revolution has its own momentum. 2026 is another year deeper into it.

For more, watch the conversation from DERVOS on Energy Dominance and the Electrostate featuring Daan Walter.

Fascinating framing of electrotech as inheriting IT's momentum. The parallel between chip manufacturing and solar/battery production really clarifies why the scale-up is happening so fast. One thing that stands out is the point about physics favoring electrons over combustion, the 2/3 energy waste in fossil systems isn't talked aobut enough when comparing pathways forward.

lol! After 25 years and $20T wind and solar represent less than 3% of energy *actually* generated and used. 2025 was a record ear for new solar/wind, yet at the 2025 rate it would take 100-400 years to displace current useful (non-heat waste) fossil energy setting aside any growth. People, look at the actual energy generated, not nameplate installed, two very, very different numbers. Spreadsheet is right here with the *real* numbers - https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review